It’s that time of year again. Journalists in every publication are boshing together a Christmas present guide for all of the literati out there. So here’s mine. Please note – these suggestions spring only from the books that I have read myself. This is not an attempt to cast a definitive verdict on the books published this year. I’m lucky to be able to read a huge number of books in my retirement, but I’m sure there are many contenders that I haven’t got round to yet. Some on the list, as the reviews make clear, are there because they are interesting in some way, rather than brilliant. With those caveats, here we go…

The Traitors’ Circle – Jonathan Freedland

My Book of The Year – and it’s not even a novel!

Freedland explores the lives of nine influential people in Nazi Germany who have severe misgivings about Hitler, the war and the whole Nazi project. They are loosely interconnected, their paths criss-crossing throughout the period, and all in some way, try to work against the regime. It’s clearly a dangerous path to choose, as anyone not fully signed up to Nazism is picked off in one way or another. Lack of preferment, prison, concentration camps, disappearances and murder in plain sight are all visited upon anyone who speaks out. It’s brilliantly constructed, with short chapters scrolling through the roster of characters Freedland establishes from the beginning, each one ending in a teaser or cliffhanger. The overall effect is one of a tightly plotted detective novel. An enthralling, thrilling read.

The Land in Winter – Andrew Miller

Listed for the Booker Prize, this is a glorious piece of historical fiction, set during the Big Freeze of 1962/63. Subtle and satisfying, this is an enormously enjoyable novel of relationships. A book for adults, as Woolf famously said of Middlemarch. If Flesh is better than this, It’ll be a great novel. But the Booker judges are nothing if not unreliable in their judgement

Long review here: https://growl.blog/2025/07/09/the-land-in-winter-by-andrew-miller/

Entitled – the rise and fall of the House of York – Andrew Lownie

This book would have been unthinkable even a few years ago, such is the iron grip the Royal family have on the British establishment. But now, open season has been declared on the ghastly Royals. They have presented a juicy target ever since the Queen died, and the tabloids have been plugging away at their pet targets: Harry and Meghan, Camilla, and Andrew and Fergie. The Mail and the Telegraph have been twisting in agonised indecision over this as performative hatred of paedophilia has vied with slavish arse licking of anything Royal. For normal people, it’s the whole corrupt lot of them. For previously arch royal sycophants, it’s worth sacrificing two embarrassing Minor Royals in the belief that the Body of Royalty as a whole might be saved by the judicious amputation of some corrupt and rotting limb.

The book is basically gossip, but it’s enjoyable reading about just how appalling these two were (and are). If it has a fault it’s that it’s just a little dull and not shocking enough. Some of the more shocking revelations Lownie treats us to are:

- Andrew routinely leaving his semen stained tissue paper scattered on the floor for staff to collect and dispose of

- Reports of forty prostitutes being shipped to his hotel room on some Trade Envoy Jolly over the course of a four day stay.

- On being told by a young woman at his table for some dinner that she was a Secretary, Andrew, horrified, replying, “How uninteresting. Is that the best thing you could find to do?”

Nice Guy. Between their divorce and The Epstein scandal, the book is reduced to a litany of descriptions of their serial affairs, financial mismanagement, and corruption. It establishes behind any reasonable doubt that Andrew is dim, privileged, entitled, boorish and utterly boring, while Sarah is a sex machine spendaholic space cadet. Still, worthwhile to have one’s prejudices so well researched and confirmed.

Ripeness – Sarah Moss

What a lovely novel this is, from someone writing at the top of their game. Structurally and stylistically, it’s a treat, with alternating sections telling the stories of the same character, Edith, fifty years apart. The younger Edith tells her own story, in the first person, through the device of a lengthy letter to a child, to be read in the future, explaining the circumstances of the child’s birth and subsequent life. The sections dealing with the older Edith are set in rural Ireland and are told in the third person. Beautiful descriptions of both the countryside around Como and small town/village life in the Republic are subtly blended with Edith’s reflections on first growing up and then getting old. Honestly, this is a must read book. Beautiful and thought provoking. Longer Review here: https://growl.blog/2025/06/05/ripeness-by-sarah-moss/

The Artist – Lucy Steed

Reading this in the depths of winter, this historical novel set in the sundrenched summer of a village in Provence is a therapeutic treat, like a session in a natural light booth for SAD sufferers. A young journalist, Joseph, suffering from the traumas of the first world war, travels to the remote home of celebrated artist, Eduard Tartuffe, to undertake a profile of him for the art journal he works for. He finds the great man sour and difficult, and living alone except for his niece Ettie. As he wins Eduard’s trust and gets closer to Ettie, secrets are revealed. A lovely book.

Crooked Cross – Sally Carson

This year’s long forgotten rediscovery, Crooked Cross was written in 1933 by an English woman Sally Carson based on her experiences on holiday in Bavaria. It tells the story of the slow build up of nazism and the way it overwhelms everyone’s lives, even in the backwaters of a Bavarian village, explaining how, in an incremental way, ordinary tolerant people can be drawn into the most despicable acts.

A timely text in the light of the current wave of racist populism that is sweeping across Europe and America. Oh no, I forgot. We’re not allowed to make any Nazi/Fascist comparisons between today’s political titans and those of the 1930s. Actually, it’s impossible not to, if you have any regard to historical facts. It’s a worthy revival, if only to publicise the parallels between then and now and between them and us, but it shows its age. Despite the subject matter, it lacks real drama and/or tension and didnt quite live up to its reputation.

Our evenings- Alan Hollinghurst

I must confess, I’ve started several of Hollinghurst’s novels, and have never liked, much less finished, one of them. It’s just one of those things – he’s lionised by the literary establishment, but for some reason, he just doesn’t do it for me. This latest got rave reviews and it starts brilliantly. There was a moment when I thought this was going to be the Hollinghurst novel where I finally got it, but unfortunately, by the end I was a little underwhelmed. But reader, I finished it! And that’s a first.

It’s a whole life story novel that follows Dave Win’s progress as a gay, half English, half Burmese actor, navigating public school, the disapproval of his family and the casual racism and homophobia he encounters. The relationship with his mother is beautifully observed, but another relationship, with the bully at school who goes on to achieve high office in a Tory government, promises much, but ultimately fizzles out without delivering. If you don’t share my antipathy towards Hollinghurst, it’s definitely worth a punt

What We Can Know – Ian Mcewan

The latest from McEwan shows his powers are undiminished, after a career at the very top of English fiction. The book is framed as an academic literary investigation, in a Britain clinging on after a series of ecological disasters in 2125, into a celebrated poet and climate change denier from the Britain of 2020. It’s a strange mixture, at times compelling, often fascinating, and at other times annoying.

The good stuff is the unrolling of the climate disaster and the unforeseen impacts that has had (Nigeria is the preeminent power, and America has disintegrated into a ferret sack of competing warlords and clans.) The bad stuff is the suffocating superiority of the middle class literary types, with their casual snobbery, all, seemingly, having affairs with anyone and everyone. I’d like to think McEwan is trying to skewer them and their ghastly attitudes, but I fear that he may actually share many of them. That’s harsh – it’s beautifully written, as ever, and worth a read.

Isla – Jim Pollard.

One of the pleasures of exploring the work of independent writers is that you come across things that deserve much greater exposure. This one’s a gem. Pollard, an ex-teacher and journalist, has specialised in books about men’s health, accumulating an impressive back catalogue, irregularly punctuated by his novels. His latest, Isla, is inspired by the Madeleine McCann case, and explores the aftermath over a lifetime of such a traumatic event. It’s set in Paris and London, and beautifully evokes both cities. There are no easy answers to the questions the novel poses and no obvious ones either. This is a great read.

Longer Review here: https://growl.blog/2025/05/21/isla-by-jim-pollard-a-review/

And you can buy it here: notonlywords.co.uk/isla

Main review here:

Tony interruptor- Nicola Barker

Barker is consistently one of the most interesting of British novelists, who deserves a much higher profile. Her books are often odd, awkward little things, and this one is no exception. It would be a delightful stocking-filler.

Seascraper – Benjamin Wood

An excellent story of a young man who lives with his mother on the grim and exposed coastline of Morecambe Bay. He scrapes a living, continuing the work learned alongside his late father, pillaging the cockle beds in the shallows of the Irish Sea. It’s hard work, alone save for his horse in all weathers. He keeps his sanity by writing and playing songs on a second hand guitar, ( all concealed from his mother) working towards playing the folk night of a local pub. His world is suddenly turned upside down by the appearance of an American film man who descends on the community researching the beach as a location for his next film. It’s a small and perfectly formed gem.

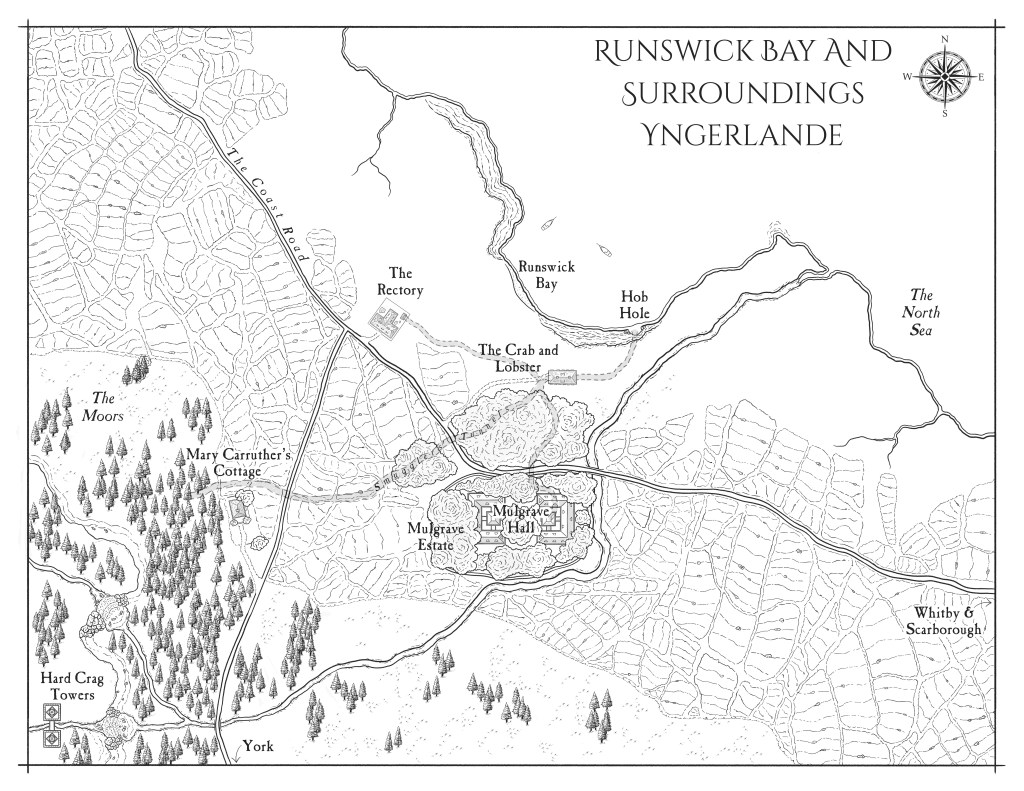

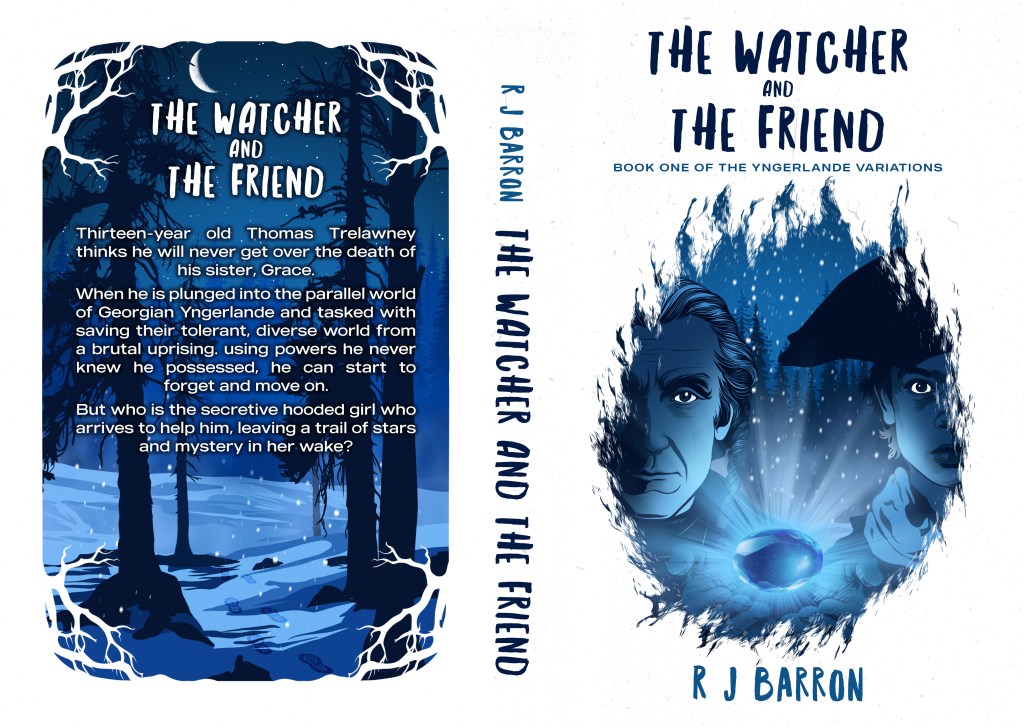

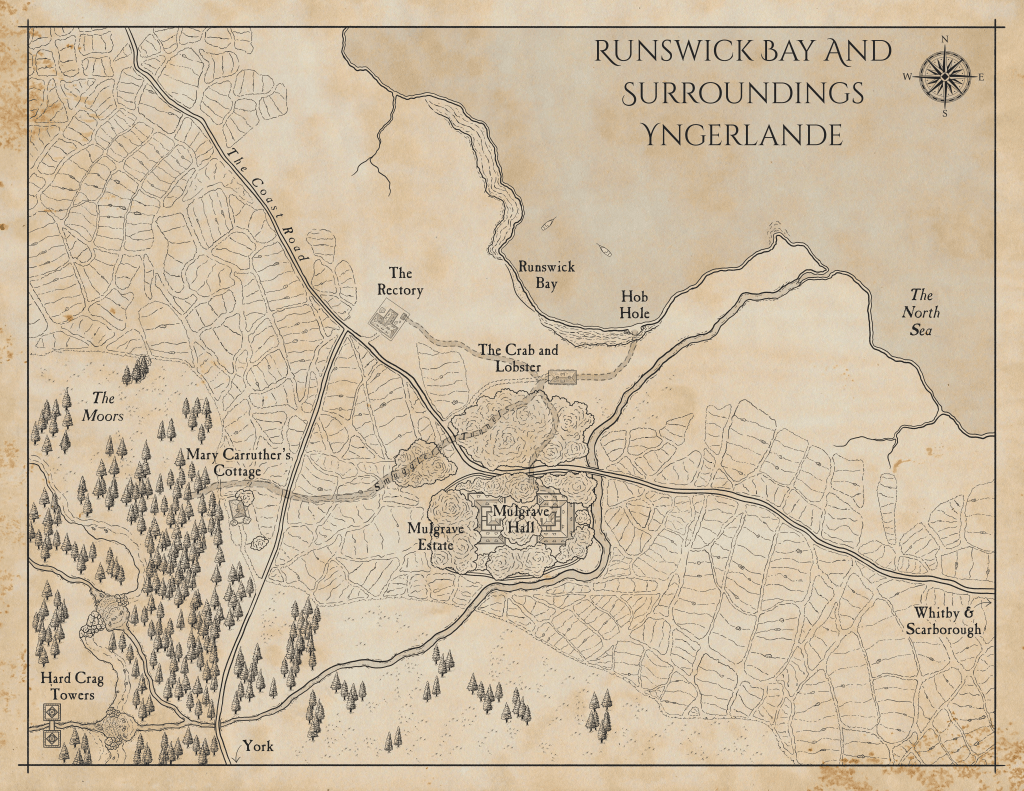

Obviously, the real book of the year is my very own, A Cold Wind Blows. The book is part 2 of a fantasy trilogy, set in Yngerlande, a parallel world to England in 1795. Yngerlande is a place of absolute and perfect equality, but their tolerance and liberalism is put at risk by an attempted counter revolution from the surviving relatives of the Old Mad King from generations before. They want to overturn all of the social advances made and establish a patriarchal, white supremacist regime. Thomas Trelawney, a thirteen year old boy from modern day England, finds himself the possessor of previously unknown powers, when he is summoned to help protect the Realm from the forces of Darkness. Think of it as Harry Potter meets Lyra Silvertongue meets Outlander. “A slice of Fantasy brilliance” said one reviewer. And they were right! You can buy it here: https://shorturl.at/UcRWb

Those that didn’t quite make it…

This could be for a number of reasons: Only just come out, I’ve heard about and intend to read, waiting for it to arrive. That sort of thing. Here they are: