* Not really…..

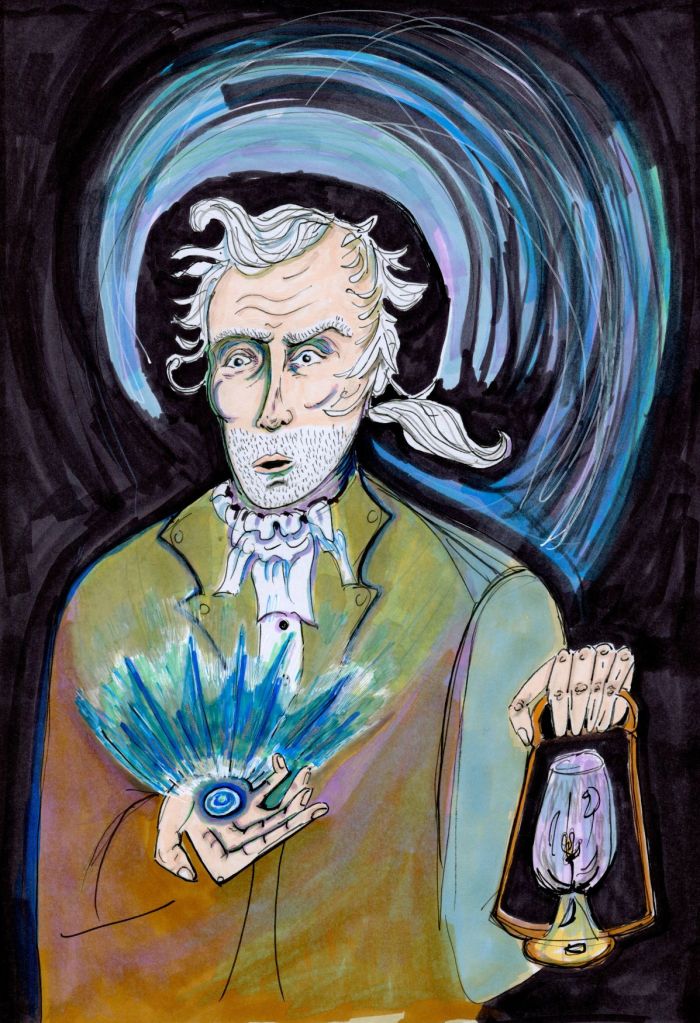

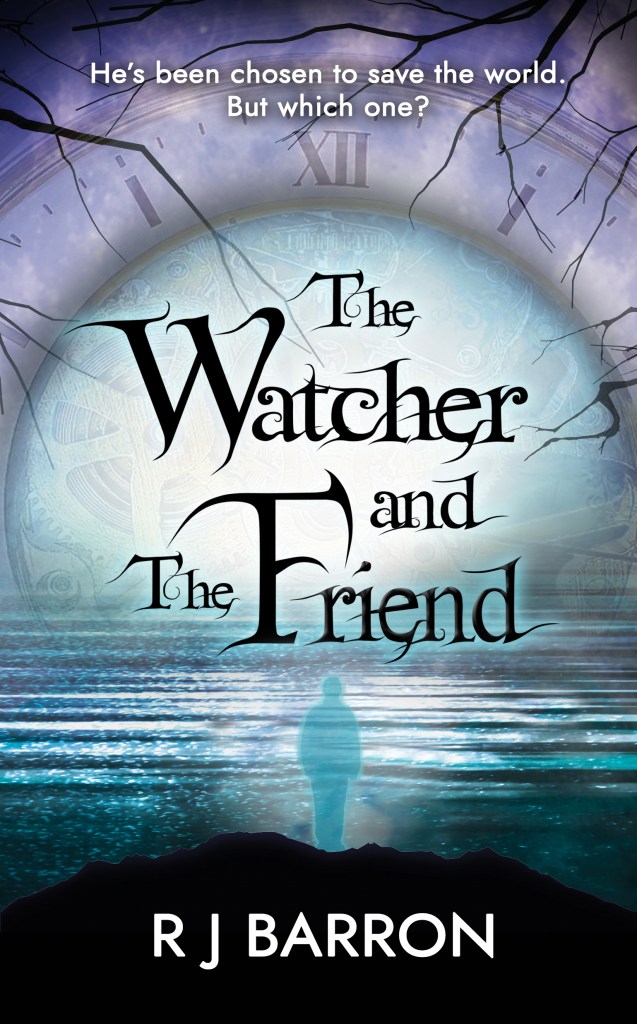

Ok, so it’s not the Booker Prize, and I’m not the only winner. But after thinking of myself at times as a Wooden Charlatan (Yes, Imposter Syndrome stalks the land of writers), it’s nice to be declared a Golden Wizard. Have a look at the review below, by the CEO of The Golden Wizard Book Prize, Louise Jane. By the way, Book 1 of the trilogy, The Watcher and The Friend, was also awarded the prize!

Review

After finishing ‘A Cold Wind Blows’ by R.J. Barron, I find it still echoing in my mind; it is such a

captivating and reflective read that stays with you.

Like the first installment in the series, this book presents an exceptional combination of young

adult fantasy and historical components, offering a distinctive and unparalleled reading journey

that you won’t encounter anywhere else. Consequently, the plot is ingenious; it is not only

fascinating but also rich in depth, brimming with thrill and drama that holds your attention from

beginning to end. It is a narrative superbly suited for the young minds of our time, who typically

thrive on continuous action and ongoing mental stimulation.

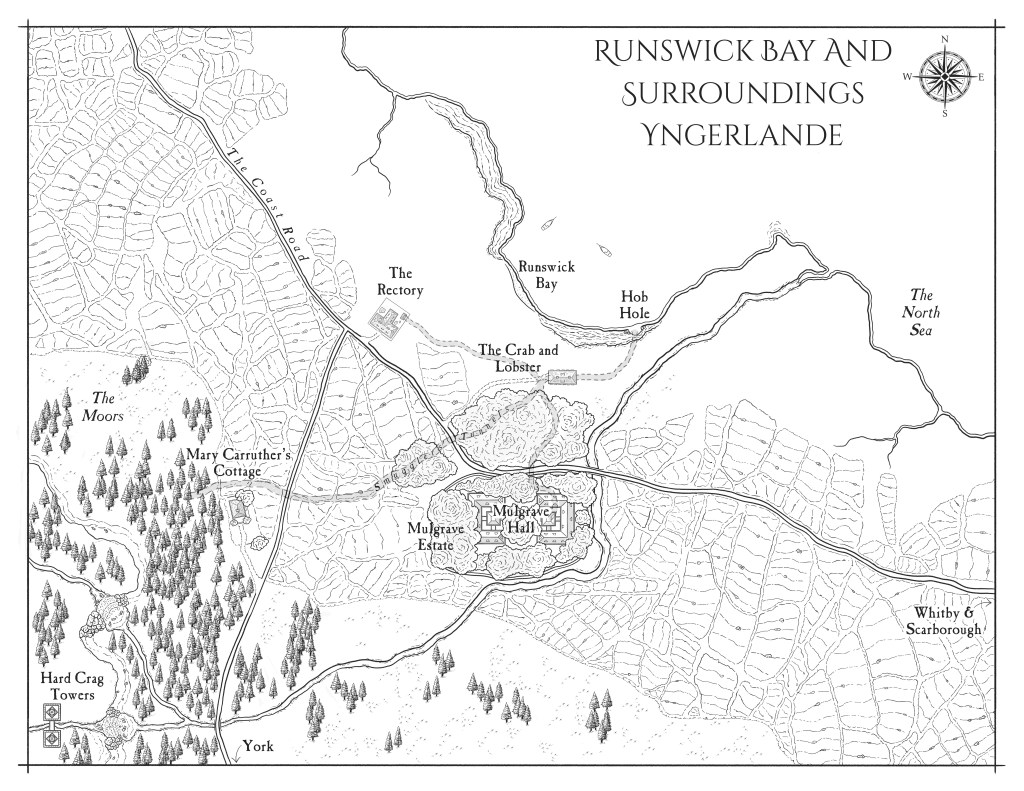

Barron’s talent as an author shines through in the detailed writing and magnificent use of

language throughout the novel. The vivid descriptions and intricate details lend a sense of

verisimilitude to the story, allowing readers to fully lose themselves in the atmospheric setting.

Similar to its predecessor, this installment captures the essence of its world, drawing readers

into a realm where every scene feels alive and palpable. The author’s ability to create such an

immersive environment enhances the overall reading experience, making it difficult to put the

book down.

I am cautious about sharing too much regarding the plot, since the story is brimming with

unforeseen twists and thrilling moments that maintain your intrigue, and I wouldn’t want to ruin

any surprises. Nonetheless, I can say that the narrative explores deep questions of loyalty and

trust, leaving you in suspense, eager to discover what unfolds next. This air of uncertainty

pushes the story onward, motivating you to keep turning the pages.

I finished the book feeling an insatiable desire for the next installment, and I highly recommend

it, especially to teens who may be reluctant readers. The excitement and tension woven

throughout the pages are sure to captivate even the most hesitant of audiences, making it a

must-read, and a series that is absolutely worth exploring!

Louise Jane, CEO Golden Wizard Book Prize

After such a glowing endorsement, it would be foolish of you to ignore it. The only reasonable response would be to buy as many copies of this book as you can, gift copies to your nearest and dearest, and use your mighty social media clout to spread the news far and wide. It would be sensible to be in on it from the beginning….