I’m reposting an old story and podcast so that new followers will get the alert. It’s a Christmas Ghost story

A ghost story for Christmas by The Old Grey Owl

Click the link below to listen to the podcast of this story:

Marley was alive, to begin with, but that’s not how it stayed. After a while, he died. This is how everyone’s story turns out, yours and mine, in the end.

They discovered the body when they finally unlocked the door to the loft, expecting to find a decaying rat or pigeon. The smell, which had steadily grown stronger over the previous weeks, was like a punch in the face when the cold, stale air billowed through the open doorway.

The old building was full of musty smells, creaking floorboards and hidden, disused rooms. They had been promising to refurbish it for years: the addition of a new block here, replacement windows there. There was even talk at one stage of razing it to the ground and replacing it with a plate glass, chromium and cedar-clad cathedral of prize-winning architect design. Staff had joined focus groups to talk to the architects and builders and pastel coloured plans had been drawn up and displayed with much pride in the old library. When the crash pulled the plug on all of the planned public sector investments, the grand schemes were quietly forgotten and the crumbling pile slumbered on undisturbed as the occasional tile or stained piece of plaster flaked and fell to the ground, as if the building was an ancient sleeping behemoth suffering from psoriasis.

It was the thing that Marley was most looking forward to about his new job. A Headship in a new school, in a gleaming new building, fit for the 21st century. Like him, he thought smugly. Fit for the 21st century. A Headteacher who had jettisoned all of those tired, ridiculous practices so common when he had started teaching. Learning styles, group work, discovery learning, thinking skills. What on earth had they all been thinking of? Marley had sniffed the way the wind was blowing early. He’d read the right books, gone on the right courses, networked on Twitter with the right people and had adopted the right poses.

The head he had first worked under, Richard Fitzwig, seemed like an exhibit from a museum now. Yes, it had been a happy place, but it’s easy to be happy when the Head lets you do what you want. Wiggy wouldn’t last five minutes in a school today. How happy would those kids be now, applying for jobs and courses on the back of crap grades? At least now, after three years of relentless focus on results and behaviour, they had something to show for it. And of course, there had been casualties on the way. Collateral damage, as he liked to think of it. Exclusions, “arrangements” for off-rolling, the endless detentions and uniform checks and silent lines and mobile phone battles. Not to mention the set piece assemblies to humiliate the ring leaders. What were they called again? “Flattening the Grass” assemblies, yes that was it. He smiled grimly at the memory.

And if many of the kids and more of the staff resented what he had had to do, then so be it. No-one had said it was a popularity contest. But, in his more reflective moments, usually alone in the small hours, he wondered. Part of him envied the easy camaraderie some of his colleagues seemed to have. And the same part was relieved he was leaving. The headship was just reward for hours of thankless work turning the school round, but more than that it was an opportunity to start afresh as the coming man in a shiny new building.

He looked around his bare flat, magnolia walls hardly troubled with pictures, shelves untouched by photos or books. A kitchen littered with a week’s worth of pizza boxes and foil trays. One Christmas card, from his mother, a bleak accusation of the lack of personal success to match his professional achievements. Not even a jokey card from Bella, for old times sake. Her poetry was for someone else now. Not that he’d ever understood it, mind you. He was a scientist, a rationalist, who chose the minimum number of words to communicate exact meaning, not nuance. She’d tried to explain it to him one day, when he was newly qualified, and it had sort of made sense then, but not any more. Nuance was for losers. Once he’d settled into his new job, the salary would mean he could buy somewhere bigger, somewhere more appropriate to his new status. And maybe then it would be worth investing something of himself in it, so it became his home, rather than an extension of his office. Whether it would be worth investing anything in anyone else was a different question. He had been badly burned last time. People always let you down, he thought, and the only way to guard against that was to keep everyone at arm’s length. Easier that way.

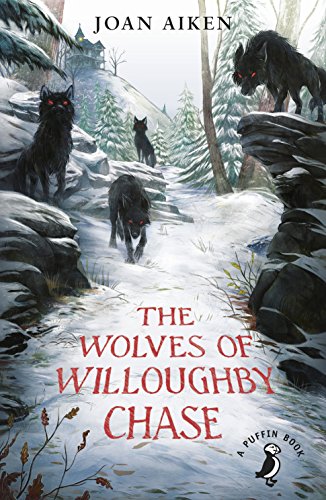

He roused himself, making a deliberate effort to shake off this dangerous introspection. Through the window he could see the blurred grey light of Christmas Eve ebbing away. There was a gust of wind and a flurry of thin snowflakes swirled across the pane. He shivered. Maybe this run was not a good idea after all. He could always leave it until January. But no, he needed to get it out of the way so he could leave the school and that life behind him, and the run would do him some good. Once he got going, he wouldn’t feel the biting wind. He reached for his rucksack, checked his laces and grabbed the keys before heading downstairs to the front door of his block.

There was already a thin dusting of snow on the pavement, and the knifing wind blew it up into dancing clouds and the beginnings of drifts in the corners. He took one final look at his watch underneath the gloves. One o’clock. He should be back in a couple of hours if all went well and the building was empty. He’d unlock and disable the alarm as usual, collect the last of his stuff from his office and most importantly, remove a couple of things from his computer, just in case. He’d intended to do it on his last day, but there had been too many people milling around, so he had resolved to wait until now, Christmas Eve, when he could be sure that he’d be the only human being in the building.

Fifteen minutes later, he rounded the corner, and saw the familiar turrets and towers of the sprawling, dirty red brick institution where he had worked for the last ten years. When he told people where he worked, they would invariably gush about how amazing it was. Hogwarts they called it. He had tried to explain the first few times it had happened that, close up, it was a dirty, crumbling, inefficient, fire hazard, but gave up when it became clear that people didn’t want their gothic fantasies to be spoiled. After a while he just smiled and nodded and agreed with them. And then, inevitably, they would move on to what a shame it was that the school had gone downhill so far and so fast, and how it was all down to the sorts of children that went there these days. He’d be glad to leave that behind as well.

As he pounded the last few metres, his breath steaming into the darkening sky, he noticed with a start that the gate was open. Turning into the car park, his worst fears were confirmed. There were half a dozen cars parked in front of the school, and the yellow lights blazed out into the gathering gloom. He pulled up, and leaned forward, his hands resting heavily on his knees, his breath coming in laboured pants and gasps.

“Shit,” he thought, “It’s open. Who the hell is in there?”

The poster on the plate glass of the entrance answered the question. The Longdon Players production of “A Christmas Carol”. Damn. Of course, how could he have been so stupid? And, yes there had been an email about it to all staff, but he had been so caught up in his leaving that it hadn’t registered. The local amateur theatre group had a two-week run at the school, before and after Christmas. They must be in doing some last-minute tweaking before they went again on December 30th.

He removed his headphones and pushed tentatively at the main entrance door. There was no-one behind the desk on reception and no signing-in book. Gary, the site manager, must have come to some arrangement with the Theatre group. He’d be hunkered down somewhere watching the football, and he’d re-emerge to switch off the lights and lock up when they had all gone. He looked up. Beyond the harsh neon lights that flooded the foyer, all was in darkness, but he could hear the distant noise of people, from the small theatre space in the far corner of the building. Good, he thought. If he slipped in and up to his office, he could avoid anyone noticing him and get away without any awkward conversations. If it took longer than he thought, he had the keys to be able to lock up again after he had set the alarm.

He switched on the torch on his phone and crept up the main staircase. If he turned on the main lights that would bring someone running, so he followed the eery, silvery light from his phone, occasionally catching his breath at the strange looming shadows it conjured up as he made his way to his office on the second floor. He had been here late at night on his own many times before and there was no doubt about it, it was a creepy place. In the wind, the building emitted the full panoply of creaks and groans and whispers, and with no lights save for the shimmering, unsteady beam from his phone, the shaky pools of darkness would have tested the most determined rationalist.

Still, that had worked to his advantage many times in the past. Being a key holder, and often on call for building and alarm issues, he had had to unlock and have a quick check many times in the past. And once in, on his own, he was free to do a little sneaking around. Hacking in to the passwords of every member of staff was child’s play for someone like him. He had never done anything criminal. He wasn’t stupid after all. But information was very powerful and he had information on everyone. He was conflicted about leaving all of this behind. One the one hand it would be something of a relief to not have that capacity in the future. As a Headteacher, he would have power of a different, more respectable kind, and it would be a triumph of sorts to have got away with some of his deceptions. But then again.

He unlocked his office and switched on the light, blinking as it pinked into life. There was a chill in the air as the seasonal shut down of the boiler had begun to take its toll. Those people down in the theatre must be freezing, he thought. He could just about hear the strains of one of the songs from the show, floating up from the rehearsal. The office was stripped down to the bare bones, with just a few reminders of the previous five years. He went over to his computer and switched it on. There, on the key board, was a Christmas card. It was sealed and addressed to “Ben Marley”.

He sat down and shook his head. What a waste of money. People were so stupid. Why on earth didn’t they just send a group email to everyone? The virtue-signallers could link it to some charity thing if they really felt the need. And the Greens could feel smug about cutting down on waste. He just didn’t want to spend money and he didn’t feel the need to dress that up in any finer motive. Christmas was just one big con.

Still, he could take it home with him and it could join the one from his mother. He ripped open the envelope and pulled out the card. A bog-standard holly and robin snow scene. At least he was spared the sanctimonious Christian nonsense. He opened it up.

“Dear Ben. Thanks for all of your hard work and support over the years. Enjoy your well-deserved promotion. Now you will really find out what it’s all about! Here’s some advice from someone who knows. Take some time and trouble nurturing relationships with your colleagues. It will help in the long run. Regards, Margaret.”

His pleasure at getting a hand-written card from the Head, who normally got her PA to do all of that for her, was soured by his annoyance at the thinly veiled criticism of her advice. Relationships indeed. She should mind her own bloody business. Maybe he wouldn’t take it home after all. He picked it up and looked at it closely again. With a flourish, he ripped it into pieces and dropped them into his bin. He’d like to think of her finding it on her return in the New Year. That would show her.

And then he saw it, just to the side of the monitor. A neatly stacked pile of what looked like more cards, all identical in white envelopes. There must have been about twenty-five of them all in the same pile. Who the hell were these from? He took the top one from the pile and examined it. In black biro in capital letters on the front of the envelope was a single word: MARLEY. The card inside had a simple message: “Fuck off and Die, you miserable bastard.” It was signed “Jack, 10B4”.

He grabbed at the second card in the pile and ripped it open. It had exactly the same message, this time signed, “Sophie, 10B4”. He didn’t bother with the others. His heart sank. All of them, every single one, hated him with a passion. Yes, he had been very harsh with them since September, but that was necessary to knock them into shape for their GCSEs. Yes, the exam specification and the league tables demanded that everyone be drilled to within an inch of their lives, and he wasn’t paid to be an entertainer or a social worker. It would be him that would get it in the neck if they didn’t get the results that the school needed. People got the sack for that kind of poor performance. There were no second chances these days.

The first flush of pain he had felt converted steadily into anger. How dare they? What cowards, to wait until he was leaving the school before they were brave enough to put their names to this outrage, after months of lessons with sullen faces brought on by screaming and shouting and eventual compliant silence. In a fit of rage, he swept the pile of cards from his desk onto the floor, before turning his attention to his computer and memory stick.

He worked steadily for a couple of hours, deleting files, copying them, and getting rid of emails. Finally, he stretched and yawned and looked away from his computer for the first time. The window was a dark square now and to his surprise it framed a blizzard of thick snowflakes. It was time to go. He rubbed away at the condensation on the window and looked outside. The show had settled and there was a couple of inches laying in the car park. There were no cars there now and, strangely, no tracks. They must have all gone before the snow had really got going. Now he came to think of it, he hadn’t heard anything from the theatricals downstairs for some time. He shivered at the sight of the snow swirling in the darkness outside. His run back home was going to be a lot more challenging than the one earlier.

He took one last look around the office, the cards still strewn across the floor, and locked the door, fumbling with his keys in the darkness. The corridor was heavy with darkness, but right at the far end, a thin yellow light leaked from the doorframe of the last classroom. This high up he could hear the wind moan and the walls creak, as if the old bones of the building were flexing in the aches and pains of accumulated years. And then, just as he was about to feel his way to the staircase, there was another noise.

He stopped and listened. There it was again. But it couldn’t be, surely? He narrowed his eyes and bent his head down towards the far end of the corridor. Yes, again. The sound of a distant child softly crying. Using the torch on his phone again, he navigated his way to the end of the corridor and flung open the door of the lighted classroom. A small boy, sitting at a table at the back of the room, jumped out of his seat in fright, shocked by the violent entrance.

His face was tear stained and he was wide-eyed and staring. He was about ten or eleven years old, and he was wearing a shabby, old-fashioned looking uniform. He held a cap in his hands.

“What on earth are you doing here? Who are you?” Marley demanded.

“Please Sir,“ stammered the boy, “I’m Ignorance. Or was it Want? I can never remember which I am. Maybe I’m both.”

He wrung the cap between his hands and wiped his runny nose on one of his wrists.

Marley looked utterly baffled. “Ignorance? Want? What are you talking about lad? And what the hell are you doing here? Who else is here?”

He scanned the four corners of the room, as if a gang of the young boy’s accomplices were about to spring out and attack him.

“No-one Sir. I am quite alone. Quite alone in the world.”

Marley looked more closely at him. He was filthy. His hands and finger nails were black with accumulated grime, and his clothes were threadbare. Marley’s frown deepened and then suddenly broke into a smile.

“Of course!” he exclaimed, “The production. You’re from the Theatre thing, aren’t you? Do they know you’re up here on your own? They’ve all gone, I think.”

The boy wiped the tears from his face. “Beggin’ your pardon Sir, but I dunno. I dunno nuffink about no theatre group.”

“What are you talking about? You must be from the production. Don’t play games with me lad. Otherwise, where’ve you sprung from? Who are you? What are you doing here?”

The boy looked up at him, his eyelashes jewelled with tears. “But I’m always ‘ere Sir. Always ‘ave been. Always will be.”

“What do you mean, ‘Always here’? I’ve never seen you before.”

“No, Sir, you ain’t. I’m always ‘ere, but you never seem to see me. No-one sees me. I sees you and I hears yer shout at the kids. Always shoutin’, never listenin’, that’s you. Not that you’re the only one, Sir, oh no. There’s plenty like you. More in the last few years, if anyfing. But you’re the worst.”

The boy pointed a bony finger at him and fixed him with his beady eye.

“You’re the worst,” he repeated.

Marley stared at him, mouth open. The chill in the room had started to bite and he shivered involuntarily.

“Is some kind of a joke?” he demanded. “Did someone in 10B4 put you up to this? “

The boy’s eyes flicked to the back of the room. There was a set of rickety stairs leading to a tiny landing in front of a door. Marley’s eyes followed the boy’s. The door led to the loft, a kind of attic space under the eaves. It had been used for storage before Health and Safety regulations prevented it. Nobody went in there now.

“They’re in the loft, aren’t they?” he demanded, a triumphant smirk on his face. “Aren’t they?”

The boy simply smiled without answering. In the silence that filled the gap came the moaning of the wind outside. It was really starting to blow hard now, and the rafters creaked and groaned as the gusts of wind battered them. Marley stared again at the door. Slowly, the handle started to turn.

“I knew it!” Marley exclaimed. “We’ll soon settle this nonsense.”

He strode up to the staircase, leaped up the five or six steps to the landing and grabbed the handle. The door would not open.

“Locked in, are you?“ he shouted through the door. “Shall I leave you in there? Wouldn’t be so brave spending the night in darkness locked in the loft, would you? You know what they say about it don’t you? Haunted it is. Haunted.”

As he was shouting these threats through the door, he fumbled with his keys. He found the right one, unlocked the door and opened it. It was pitch black inside.

“Come on out,“ he called into the room, “ You’re caught. You might as well give up now before you make things worse for yourself.”

He reached for the light switch which was outside the loft on the balcony and pressed it. The loft space was suddenly flooded with white-bright lighting, revealing the cobwebbed beams and dusty floorboards inside. There was a sound of scuffling, as if a rat had scuttled away into a distant corner. Marley stepped inside.

“I know you’re in here,” he said in a raised voice. “Just come out from where you’re hiding so we can get this thing over with.”

There was a sharp chill to the air inside and the wind in the darkness beyond was howling steadily now. He took another step inside. There was a sudden noise behind him. He whirled round to see the boy, still holding his cap, out of his seat and standing just outside the doorway on the landing.

“What are you doing? You’re not helping, you know” Marley said. “You kids, you’re your own worst enemies sometimes.”

The boy smiled at him, his tear-tracked, dirty face lit up like a beacon.

“Sometimes,” he repeated.

There was a sudden gust of wind and the timbers of the loft screeched and shifted. The door, caught in the blast, slammed with a tremendous bang. The boy turned the key in the door, reached for the light switch and the loft was plunged into inky darkness.

*

In the darkness outside, all was still and the sky was full of fat snowflakes gently floating down. The wind of earlier had subsided completely and the thick layer of snow on the ground muffled all the sounds of traffic. Gary drew the entrance gates shut, pulled off his gloves and fiddled with the padlock and key, cursing against the cold.

“Bloody theatre company. A no show on Christmas Eve. That administrator bloke must think I was born yesterday, saying he hadn’t sent any email booking a rehearsal.”

He paused, struggling to get his gloves back on over his frozen fingers. “Still,” he smiled, “It’s not all bad. Double time is double time, whether anyone showed up or not.”

*

Several weeks later, Gary was in his office taking the detectives through the CCTV footage of the holidays. They finally located Christmas Eve, and there, in grainy black and white, was film of Marley walking across the car park. Walking next to him was what appeared to be a young boy, from the theatre group, dressed as a Dickensian urchin. From the moment the camera picked him up until he entered the building, Marley didn’t turn or appear to talk to the boy. It was almost as if he did not know he was there.

They ran the film on, hoping to see someone, anyone, leave the school later. There was nothing. “That kid must still be in the building, “ said the senior detective on the case, a balding, corpulent man who gave the impression that he’d really rather be back in his warm office tidying up paperwork.

“But who is he?” asked Gary. “I’ve never seen him here before.”

The detective raised an eyebrow. “I think the question is, ‘Where is he?’”

In the months that followed, there were several TV appeals, posters all over the neighbourhood, and an extensive search of the school. The boy, whose blurred image stared out accusingly at anyone who chose to look, was never identified, nor found. Eventually, they were all discreetly taken down, discoloured and tatty by this time, as if people did not want to be reminded of the harsh realities of the world for which, somehow, they felt they were unfairly being made responsible. More comfortable to take them down, rather than look away.

When the police left, with cursory thanks and platitudes, Gary was left alone in front of the screen. He scrolled back to the point when Marley and the boy entered the school, and, on a whim, switched to one of the other cameras on the feed, pointing out from the main entrance, towards the front gate. There they were again, together but entirely separate, walking through the steadily mounting snow. And then he stopped. He froze the final shot. There on the screen, stretching back from the entrance to the main gate, like a line of punctuation marks, was a track of footprints.

One line for two people.

He stared, and shivered, as the wind rattled the panes of his window and the bones of the building creaked and groaned.

The Old Grey Owl

@OldGreyOwl1

oldgreyowl.57@gmail.com