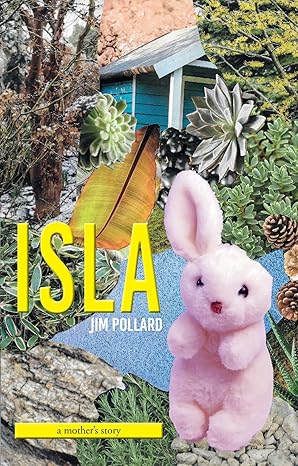

This novel should be number one on your summer reading list this year

Isla, the new novel from award winning writer, Jim Pollard, is a real treat. It tells the story of Isla Shaw, a student in London in 1983, taking us through the formative events of her life up until 2018. She shuttles between London and Paris between those years, in pursuit of jobs, relationships and some sense of meaning and contentment. It’s an intricate portrayal of a life as a series of seemingly random yet connected scenes, with twists and turns resulting from decisions taken or not. There’s no smooth character arc here. Stuff happens and Isla deals with it, sometimes well, sometimes disastrously, but always with a sense of being true to herself.

The random nature of life is emphasised by Pollard’s clever use of structure. After a fairly conventional linear opening, the story splinters into pieces taken from the immediate future and the medium-term future. The reader is left to do a lot of work reconstructing events, trying to ascribe cause and effect in the relationship between events. Occasionally the reader is given a banister to hold on to, when a chapter is headed by a date and a location, but you soon get used to not being able to rely on that every time.

The book is set up to deliver a story of how someone can recover from a devastating event in her life, charting her progress through the aftermath, but then, without warning, it does a somersault and shifts into detective mystery territory. The shift comes out of the blue, and revitalises the narrative drive of the story.

There are many notable pleasures in the novel. The evocation of Paris seen from the perspective of a damaged newcomer, grappling with a change of culture and language is very well realised. The atmosphere of Parisian cafe culture, both glossy and a little more alternative, is seductively rendered, leaving one scouring the internet planning your next Eurostar trip.

The same is true of the character’s reflections on life and love. Because of the first person narrative, most of these reflective passages are Isla’s reactions to the events as they happen to her. Pollard takes a risk with this. In a lesser writer’s hands, they would degenerate into discursive rambling that actively dilutes the forward momentum of the plot, but Pollard manages the balance between action and thought superbly well.

This is partly achieved by the empathy he has created for Isla. We are interested in her thoughts about the world, both her own little world and her relationships, and the wider world of politics and events. From the beginning, her’s is a completely believable, authentic voice that both changes over time as life batters her and essentially remains the same. In that, and in so many other aspects of the book, the writing is wise and insightful. Isla’s journey, via therapy and relationships, with detours into the cul de sacs of drink and drugs, champions the notion of the value of a life examined. “Talking about it” emerges as one of the few reliable routes to stability and contentment. And not even that provides guarantees.

A lovely book, more than worthy of your time this summer. Available in bookshops and online including Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Isla-Jim-Pollard/dp/0995656304 ) but it’s easier and quicker to buy direct from the distributor at: notonlywords.co.uk/isla

Buy it, read it, and spread the word.