A major disappointment as the metaphors run out of road.

Spoiler Alert! Unhelpful plot revelations ahead!

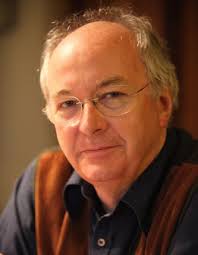

A new book by Philip Pullman is usually something of a treat. A literary event in fact. This one has particular significance – it’s the concluding volume of the Book of Dust trilogy, and as he gets older (he’s 78 now) there is always the fear that it is the last he will ever write. Before I go any further, it’s only right that I reveal myself to be a massive fan. Pullman is one of my literary heroes and an inspiration as far as my own writing is concerned. The Northern Lights trilogy is fully deserving of all the plaudits heaped upon it, not least for the fact that, by the end, it has become one of the all time great love stories.

So it’s with some sadness that I have to report that The Rose Field is a major disappointment. It’s full of lovely writing, and Pullman’s imagination (a key consideration in the light of one of the book’s themes) is in full working order, but as a coherent piece of story telling, it fails to land.

It comes in at a baggy 620 pages long, and I got the impression it could have just as well have finished after 1,620 pages, and we still wouldn’t have been anywhere near a satisfactory conclusion. Pullman, as a Great Man of Letters, has now achieved the status of “He Who Cannot Be Edited”. Pity the poor editor assigned to the task: “Phillip, do you really need all those bits with the characters discussing Dust?” is a question only a very brave soul, with no aspirations to a long term career in publishing, would ask. But it is the question that shouts out of almost every page. By the time we get to page 554 and Lyra and Malcolm start discussing Binary Absolutism, it’s screaming.

Equally unfortunately, lots of other things emerge, trade winds that blow the good ship Narrative off course, time and time again. Crucial developments occur completely out of the blue – the fact that the loathsome Olivier Bonneville is the half brother of Lyra is revealed towards the end, seemingly as another device to keep the pot boiling. Minor characters emerge and then disappear. Supposedly important characters do exactly the same. (I’m thinking of Leila Pervani here). Two thirds of the way through the book, the narrative drive of the book appears to suddenly come from a “battle” against a character who has sprung out of nowhere, the sorcerer, Sorush, involving armies of various creatures. There doesn’t appear to be any plausible reason for this development in terms of characters, relationships, or previous events, and is there simply to add a bit of action to keep the reader engaged. It seems Pullmann has taken a leaf out of Tolkien’s book, and emphasised the “quest” aspect of the story with this out-of-kilter battle. Oh the irony, after Pullman’s much discussed dismissal of Tolkien as being “thin” and not being about much. This is what he says about The Rose Field himself: “I think of The Rose Field as partly a thriller and partly a bildungsroman: a story of psychological, moral and emotional growth. But it’s also a vision. Lyra’s world is changing, just as ours is. The power over people’s lives once held by old institutions and governments is seeping away and reappearing in another form: that of money, capital, development, commerce, exchange.”

That’s one of Pullman’s greatest difficulties here. He makes the key mistake of thinking he is writing about something and Something Very Important at that, so the story takes a back seat. Tolkien could teach him a thing or two about telling a compelling tale.

All of this adds to the impression that Pullman is desperately trying to write himself out of several of the corners that the first two (five?) volumes have backed him into. One of these is the growing relationship between Lyra and Malcolm Poulstead. The awakening of friendship into love is something Pullman has form on. The changing of the relationship between Lyra and Will in the Northern Lights trilogy was beautifully done, and forms the backbone of the books. He attempts the same thing here, using the daemons of these two characters to add depth and subtlety to the development. Once again, it’s really well done (apart from the nagging suspicion he’s re-treading old ground), but then, right at the end, he pulls the rug from underneath his readers. It’s as if he’s just realised that the relationship between two characters who are eleven years apart in ages, where Malcolm used to be Lyra’s teacher, could be deemed a little problematic, a little too groomy. In one conversation, right at the end of the book, he trashes all of the careful build up, by having Pan tell Lyra that Malcolm was in love with Alice and that they (Pan and Lyra) “will have to put the idea in his head”. Job done. One more loose end tied up as if by magic.

There’s similar botching when it comes to explaining Dust, “Alkahest”, Rose oil and Pan’s decision to leave Lyra at the end of The Secret Commonwealth to go in search of Lyra’s missing “Imagination”. It’s bound to fail, because they are ideas born of beautiful, powerful,vague metaphors. Their power and beauty comes from their very vagueness – that’s how metaphors work – through association and connotation. The minute you try to rationalise them, their power and beauty drain away and they are left like the Wizard of Oz after the curtain is ripped aside – small and a little pathetic.

By the end of the book I was torn. I couldn’t make up my mind whether Pullman should have stopped after finishing Northern Lights and turned to something completely new, or whether I should be grateful he started The Book Of Dust for the pleasures it produced. The trouble is that once you have set the bar so high, it’s a very long way to fall when you don’t quite get it right the second time around. Maybe it’s time to write another Ruby in The Smoke – short and punchy, and not a binary absolute in sight.