Writer walks into windowless, dusky room and switches light on. Room gets darker. The End

I’d been meaning to read The Kellerby Code since the beginning of Summer. I’d noticed a few references to it in the weekend supplements, and then it began to be more heavily promoted with Richard Osman’s one word verdict: Genius. On further investigation, it seemed that the book was a comedy, set in a Country House, with shades of Evelyn Waugh and P G Wodehouse. It sounded delicious, just right for two weeks away in the Mediterranean sun.

Such is the power of marketing – selling a book in shedloads, even though it falls apart virtually the minute you begin to read it. Its only possible virtue is its future role in Creative Writing courses as a manual on how not to write a novel.

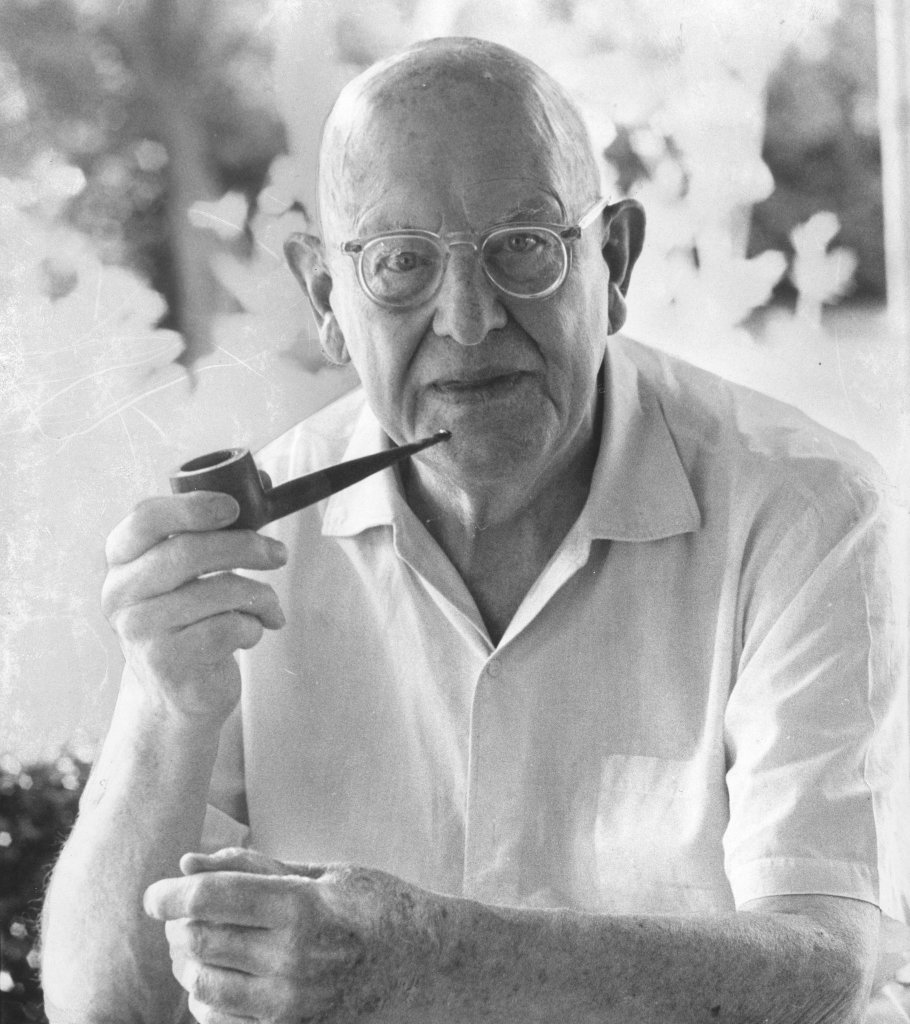

I know this sounds cruel. After all, it is Mr Sweet’s debut novel and budding writers need gentle encouragement, but I really think you can put away your sympathy and save it for more deserving cases. He has, after all, sold millions, made a fortune, and has nicely set up a second career to slot alongside his night job as a Stand Up comedian, probably now with a multi book follow up deal.

The TV adaptation can’t be far away. And, to be honest, that will probably be much better than the book, because no one would have to read it and…….How can I put this politely? This is very, very badly written. Thankfully for you, dear reader, I’ve already read it, so that you don’t have to.

SPOILER ALERT!

(But actually, dont worry, You’re never going to read this book…)

Although both Brideshead and Blandings are both referenced in the book, and the title is an echo of The Code of the Woosters, the real comparisons are with the film, Saltburn, and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley. It’s about a lower middle class young man, Edward Jevons, who falls in with a posh, entitled, aristocratic set at Oxford, whose leader, Robert, takes him under his wing and simultaneously patronises and exploits him. The gilded crew naturally fall into highly paid jobs in the arts and finance, via their discreet network of patronage and influence, while Edward, embarrassing oik that he is, is reduced to tutoring the ghastly offspring of the Chelsea and Knightsbridge elite. His real job, however, is to be Robert’s unofficial factotum and gopher, being expected to fulfill a myriad of trivial bits of domestic administration, unpaid, at the drop of a hat. This is done under the heading, Friendship, apparently, because Robert is grappling with the higher problems of being an up and coming theatre director and has no time to wipe his own arse and he doesn’t much care for getting his hands dirty.

Edward is completely besotted with this world, leaving his roots behind him, and is completely blind to the fact that his new posh friends actually despise him, and refer to him as Jeeves behind his back. The situation is complicated by the fact that he is totally in love with Stanza (yes, really), more posh entitled totty who treats him like dirt and things really begin to take off when Robert starts going out with her and eventually marries her. The second half of the book brings a murder, which is the trigger for Edward’s descent into nervous breakdown territory and several more, ludicrous murders.

The plot is actually quite engaging, and even when the coincidences and hugely overblown prose threatened to make me chuck the book against the wall and admit defeat, wanting to have narrative resolution kept me going. The characters are uniformly ghastly. I read the whole book without incurring any warm feelings or concerns about anybody – not the vile poshos, and certainly not the wholly pathetic Edward, whose whinings and self pity produced a dreadful toxic cocktail of a personality that was more repellant than sympathetic. In the end, I felt the Bullingdon club crowd were actually too nice to him

The “twists” and “turns” of the plot were laughably poor. At times we were asked to believe that Edward, presumably our hero, had never read or seen a contemporary detective drama and was completely unaware of CCTV, DNA, fingerprints or even the basic fact that the police might ask him some questions and then triangulate his answers against what other witnesses/suspects had said. None of it matters though – there are so many loose ends and plot holes, so many inexplicable decisions made, that the real pleasure of the book was seeing what the next ridiculous plot twist was going to be. The concept of suspending disbelief was taken to new heights, such that in the end it became not a matter of suspension of disbelief but total disappearance of belief. This is a book that rests entirely on blind faith, like a religion, but without the rewards religion purports to offer. Textual Fundamentalism is the way forward. It stops hard pressed writers having to give a second thought to all those tiresome ideas about credibility, motivation, or authenticity.

But the worst is yet to come. My God, the prose, dear reader, the prose. The analogy that pushed its way into my consciousness, as I was ploughing through this car crash of a book was that of the IKEA flat pack piece of furniture. You get the damn thing home and open it up, and then diligently read through the language-less instructions.

Bolts and screws of various sizes are included in separate plastic bags, but it’s not until you have nearly constructed the thing that you realize that it doesn’t fit together and that you’ve used the wrong screw for the wrong bit of MDF. Here, Mr Sweet discovered that he’d been sent a big bag of commas and a tiny bag of full stops.

Sentences stagger on, many clauses lashed together by commas, desperately searching for a full stop, until they collapse, bleeding and exhausted. This is someone with a nice turn of phrase and a vocabulary that they are secretly very proud of, but who is determined to show you everything they can do. In every sentence. Every time. As a former GCSE and A level English teacher, my greatest priority was to impress upon my students the utter beauty of the short sentence, and the absolute necessity of a variety of sentence lengths and structures, so that there was some sense of rhythm to the whole thing. So that it sounded good when read aloud and felt nice in the mouth. Here, it sounds like radio static and tastes like a mouthful of Brylcreem. Back in the day, if little Jonny were one of my students, his submission would have tested my powers of constructive feedback and diplomacy.

My sincere suggestion to you, dear reader, is don’t bother with this. Watch Saltburn instead. Or watch and read The Talented Mr Ripley. And for advice on how to write sublime sentences, read some Wodehouse. You know it makes sense.